Long way towards dignified menstruation for women in India

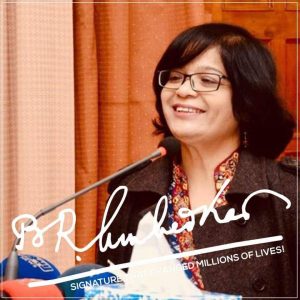

By Manjula Pradeep, Indian human rights activist and a lawyermanjul[email protected]

Menstruation and the taboo associated with it is still an Indian reality. It has created difficult situation for

Indian women further being treated as second class citizens in the country. 355 million is the number of menstruating women in India, accounting for nearly 30 per cent of the country’s population. Menstruation continues to be a subject of gender disparity in India[1]. The social stigma or exclusion on the name of deep rooted issue of impurity associated with menstruation a cycle of neglect internalize cultural myths and stereotypes associated with menstruation which undoubtedly influence practices and behaviour directed towards menstruation[2].

A taboo is a strong social prohibition or ban relating to any area of human activity or social custom that is sacred and forbidden, based on moral judgment and sometimes even religious beliefs. Breaking the taboo is usually considered objectionable by the society. Menstrual taboo is one such widespread social taboo. It is no wonder that primitive religions incorporated taboos around the menstrual process. There are many religions, which to this day, hold primitive ideas and beliefs regarding this common phenomenon. Hinduism views the menstruating woman as impure or polluted and is referred to in some places to have a curse. The impurity lasts only during the menses, and ends immediately thereafter. Formerly during menstruation, women used to leave the main house, and live in a small hut outside the village. They were not allowed to comb their hair or bathe. In other words, menstruating women did not have access to water when they needed it for personal hygiene. Some recent studies witnessed prohibitions to cook food, and provision for separate utensils. Entry to the prayer room within home and the temple is strictly forbidden. A woman experiencing her period cannot be part of religious ceremonies for the first 4 days of the cycle. Muslim culture advocates that menstruating women should be avoided by men. Though Islam does not consider a menstruating woman to possess any kind of contagious uncleanliness, but do treat menstruation as impure for religious functions. There are two main prohibitions placed upon the menstruating woman. First, she may not enter any shrine or mosque. In fact, she may not pray or fast during Ramadan while she is menstruating. She may not touch The Quran or even recite its contents. Secondly, she is not allowed to have sexual intercourse for seven days (beginning when the bleeding starts). She is exempted from rituals such as daily prayers and fasting, although she is not given the option of performing these rituals. In Buddhism, menstruation is generally viewed as a natural physical excretion that women have to go through on a monthly basis, nothing more or less. However, Hindu belief and practice has carried over into some categories of Buddhist culture, under the influence of which, menstruating women cannot meditate nor can they have contact with priests. They cannot take part in ceremonies, such as weddings. There is also a Buddhist belief that ghosts eat blood and a menstruating woman is thought to attract ghosts and is therefore a threat to everyone around. In Sikhism, a woman is given equal status to man and is regarded as pure as man. The Gurus teach that one cannot be pure by washing his body but purity of mind is the real pureness. They are not called pure, who sit down after merely washing their bodies. Besides Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism also condemned the practice of treating women as impure while menstruating. The similarities among the major religions regarding their beliefs about menstruation are striking. Some of the more consistent themes include isolation, exclusion from religious services, and restraint from sexual intercourse. The difference between the major religions lies in the level of severity of the menstrual taboos. Buddhism and Christianity offer a lenient view of the menstruating woman[3].

My understanding about menstruation as a Dalit woman started the day I started my menstruation. I was around 13 years old and I was not given any information or education about menstruation. I was given an old piece of cotton cloth with a string to tie around by waist and cloth to be put between by thighs. I realised that I was seen with different eyes by my mother and other family members. I was born in a Hindu Dalit family. Hence I was told not to go close to the place of worship, not to touch the bottle of pickle, etc. I also felt embarrassed to wash and dry my menstruation cloth in the open space outside my house. My mother would tell me that after the fourth day, I should wash my hair and make myself pure. My father who was a government officer did not bother to give money for me, my sister and my mother to buy sanitary pads. It was almost 8 years that I used an old cotton cloth as a sanitary pad. The time I started earning myself, the first thing I brought was sanitary pads.

Lack of awareness makes for a major problem in India’s menstrual hygiene scenario. Indian Council for Medical Research’s 2011-12 report stated that only 38 per cent menstruating girls in India spoke to their mothers about menstruation. Many mothers were themselves unaware what menstruation was how it was to be explained to a teenager and what practices could be considered as menstrual hygiene management.

A 2014 report by the NGO Dasra titled Spot On! found that nearly 23 million girls in India drop out of school annually due to lack of proper menstrual hygiene management facilities, which include availability of sanitary napkins and logical awareness of menstruation. The report also came up with some startling numbers. 70 per cent of mothers with menstruating daughters considered menstruation as dirty and 71 per cent adolescent girls remained unaware of menstruation till menarche. Indian Council for Medical Research’s 2011-12 report stated that only 38 per cent menstruating girls in India spoke to their mothers about menstruation. Many mothers were themselves unaware what menstruation was how it was to be explained to a teenager and what practices could be considered as menstrual hygiene management. Schools were not very helpful either as schools in rural areas refrained from discussing menstrual hygiene. A 2015 survey by the Ministry of Education found that in 63% schools in villages, teachers never discussed menstruation and how to deal with it in a hygienic manner.

Surveys by the Ministry of Health in 2002, 2005, 2008 and 2012 found out that most problems related to menstrual hygiene in India are preventable, but are not due to low awareness and poor menstrual hygiene management. This resulted in development of some serious ailments for adolescent girls. Roughly 120 million menstruating adolescents in India experience menstrual dysfunctions, affecting their normal daily chores. Nearly 60,000 cases of cervical cancer deaths are reported every year from India, two-third of which is due to poor menstrual hygiene. Other health problems associated with menstrual hygiene like anaemia, prolonged or short periods, infections of reproductive tracts, as well as psychological problems such as anxiety, embarrassment and shame.

The typical superstitions which lie around for a menstruating Indian woman are:

– Apshagun i.e. (bad omen) if the men see a menstruating woman before they leave for work.

– The used menstrual cloth possesses an evil quality and men could go blind if they see it.

– If a dog digs out a used menstrual cloth buried in the ground, the woman who used it will become infertile[4]

Vulnerably positioned at the bottom of India’s caste, class and gender hierarchies, Dalit women experience endemic gender-and-caste discrimination and violence as the outcome of severely imbalanced social, economic and political power equations. Their socio-economic vulnerability and lack of political voice, when combined with the dominant risk factors of being Dalit and female, increase their exposure to potentially violent situations while simultaneously reducing their ability to escape. Violence against Dalit women presents clear evidence of widespread exploitation and discrimination against these women subordinated in terms of power relations to men in a patriarchal society, as also against their communities based on caste[5].

One of the cruellest forms of violence against Dalit women is Devadasi practice i.e. forced temple prostitution, where young Dalit girls when they start their menstruation are offered as Devadasis to temples where they are sexually abused and raped by dominant castes men in their villages. This practice is still in prevalent in Southern states of India namely Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka and on the periphery of Maharashtra state.

But it’s a different treatment for the girls from dominant castes in South India. Once the girl attains her puberty, her family informs all their relatives and friends about the celebration. The celebration can be big or small in size and extravagance; it totally depends upon how the family chooses to celebrate it. Friends and Relatives attend this function and give wonderful gifts and blessing to the girl, post which they enjoy a grand meal[6].

But it’s the same India where women had to fight legal battle to enter a Dargah, a Mosque and a temple. There are around ten of them which have banned entry for women. In an article by Meghna titled “No Entry for Women in these Temples of India” the names of religious places banned for women are Shree Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Kerala, Ayyappan Temple (Sabarimala) in Kerala, Jain Temple in Ranakpur, Rajasthan, Jain Temple in Guna, Madhya Pradesh, Patbausi Satra in Assam, Guwahati, Shani Shingnapur Temple in Maharashtra, Haji Ali Dargah in Mumbai, Maharashtra, Jama Masjid in Delhi, Nizamuddin Dargah in New Delhi and Idgah Masjid in Shillong, Meghalaya.

On September 28, 2019, a five-judge Constitution bench, headed by then chief justice Dipak Misra, lifted the ban on the entry of women of menstrual age into the Sabarimala temple sparking widespread protests by Hindu groups across Kerala. The five-judge Constitution Bench had junked the age-old tradition of the Lord Ayyappa temple by a majority verdict of 4:1. The temple which opened its doors for a five-day monthly pooja on October 17, 2019 witnessed massive protests by various devotee groups and Hindu outfits against the Pinarayi Vijayan government’s decision to implement the apex court order without going for any review petition[7].

The Haji Ali Dargah Trust, which initially resisted women’s entry after a ban was put in place in 2011-12 and which filed an appeal before the Supreme Court, conceded in October 2016 that women can enter the sanctum[8].

But for Dalit women, struggle for dignity becomes more challenging and difficult. The lower-class women do not have a break for rest during the menstruation from housework and their physically tedious work as manual scavengers, construction worker or agricultural labourers[9]. They are treated as untouchables by the dominant castes, but their defilement as a menstruating woman takes a backseat when they are at different work places as their caste identity is more visible than their menstruation. Hence the issues and problems relating to Dalit women and girls always remain at the margin so as dignified menstruation. Dalit women’s caste, class and gender take them away from living a dignified life and dignified menstruation for them is long way to go.

[1] Menstrual Hygiene, Women’s Day Special –Written By: Saptarshi Dutta | Edited By: Sonia Bhaskar

[2] A KAPB study report Menstrual hygiene & Management, Vatsalya – WaterAid, 2012

[3] A Dialogue on Menstrual Taboo Article in Indian Journal of Community Health · June 2014

[4] Garg, R et al. (2011). India moves towards menstrual hygiene Subsidized Sanitary Napkins for Rural Adolescent Girls-Issues and Challenges

[5] Dalit Women Speak Out – Violence against Dalit Women in India- 2006, Aloysius Irudayam s.j. Jayshree P. Mangubhai , Joel G. Lee, 2006

[6] Puberty Ritual in South India, Meghna · May 26, 2016

[7] https://www.thestatesman.com/india/women-entry-sabarimala-not-stayed-sc-refers-review-pleas-larger-7-judge-bench-1502821823.html

[8] https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/mumbai-haji-ali-dargah-women-entering-inner-sanctum-sabarimala-supreme-court-5408259/

[9] Can We Really Discuss Menstruation in India Without Talking about Caste? Sowjanya Tamalapakula, 28th May 2020